-

biomenstrual pads

Menstrual blood is blurring the boundaries of the human body. Once this blend of blood, mucus, and tissue leaves our bodies, we wonder if it is no longer part of us, where it goes, who it might nourish or harm, what more-than-human bodies it might encounter.

The practice of using blood as a fertilizer prompts us to imagine how we might design to re-use or compost our bodily waste, together with biomaterials that might aid with absorbing and collecting menstrual blood. What would future menstrual pads look like if we designed for these practices? Which species would be entangled with human menstrual care?

-

Exploring superabsorbent biomaterials

Sanitary pad and tampon prototypes made with gluten

Sanitary pad and tampon prototypes made with glutenDuring the last few weeks we’ve been meeting with Antonio Capezza, PhD in Fiber and Polymer Technology at KTH Royal Institute of Technology and Product Quality at SLU, currently doing his postdoc in the same topic, with a focus on protein-based superabsorbents for the hygiene industry —funded by Bo Rydins Stiftelse for independent research. Antonio’s work is motivated by finding a sustainable and biodegradable replacement for SAP (Superabsorbent polymer), which is a plastic-based superabsorbent that turns into a viscous gel when in contact with liquid. This fossil-based material is non-biodegradable and can lead to toxic waste and microplastic pollution.

-

Soil chromatography

“I would dip my dumplings in that!” —Marie Louise when seeing one of the samples to test, a (non edible) orange mix of flower petals and sodium hydroxide that resembled sweet and sour sauce.

Soil chromatography is a practice to qualitatively measure the fertility of soil. We invited Anton Poikolainen Rosén, who has been using this technique with urban farmers in Stockholm, to share this process with us and test several samples of soil and organic matter.

-

Machine learning, mosses, and gynecology

GyneGAN

GyneGANThis blog entry is documenting early design explorations of how machine learning could be used to attend to more-than-human and multispecies menstrual care. ML and AI are not innocent technologies. Rather, as revealed by e.g. Kate Crawford and Joy Buolamwini, the material infrastructure of ML/AI are damaging the environment, and the embedded bias and logics are perpetuating social inequality through sexist and racist recommender and face recognition systems. By using ML in design explorations with menstrual care, I seek to both disentangle and grasp these politics and — if still possible — imagine feminist and more-than-human utopian uses and applications of ML for purposes that nurture both society and planet.

-

From biomaterials to compost

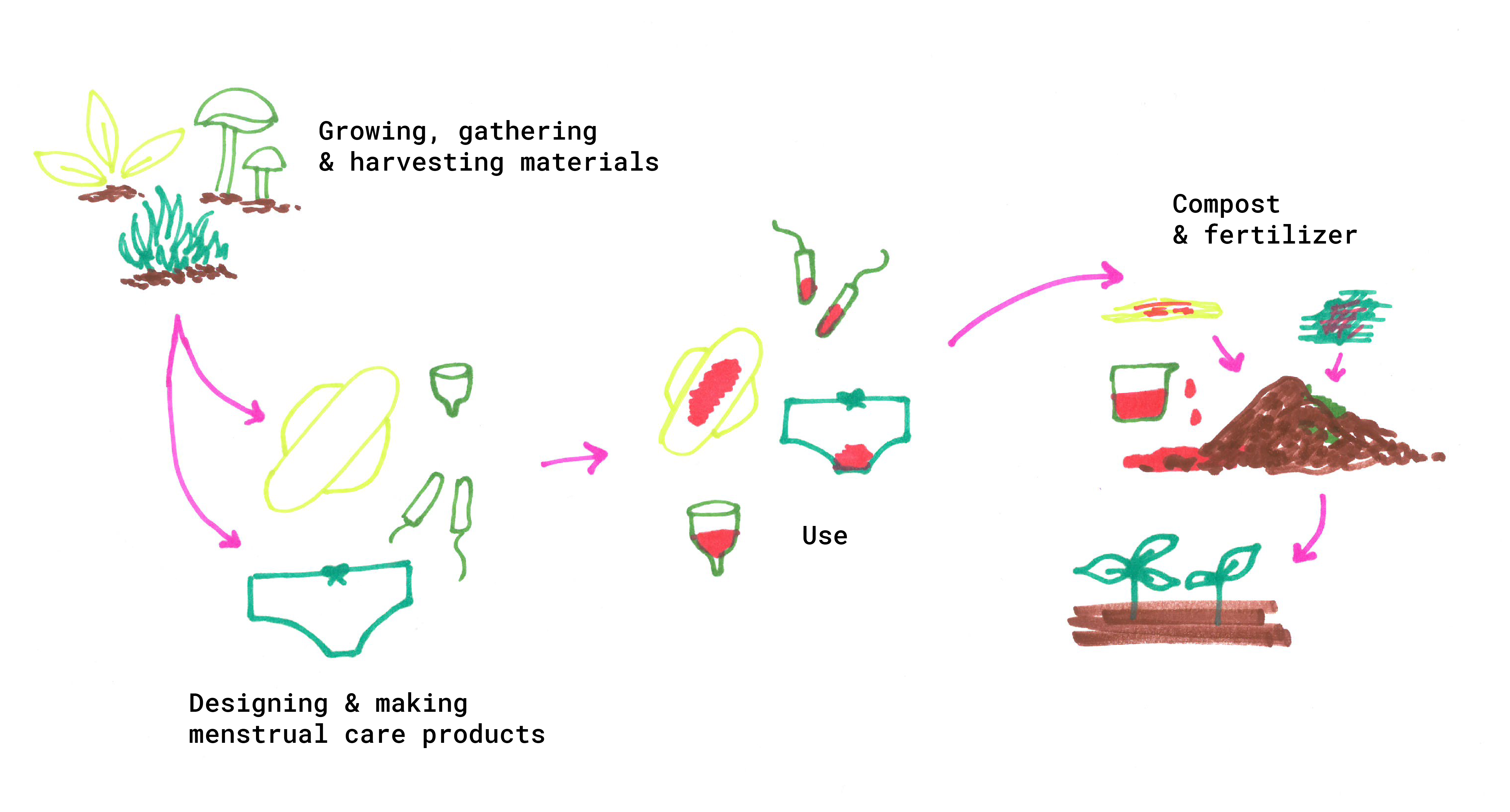

When mapping out the design space of this project I found it easier to define a few stages or steps in the lifecycle of imagined sustainable menstrual products. Our designs will address one or several stages of this process.

-

The process begins with the growth, gathering or harvesting of biomaterials, coming from plants, fungi, or other micro or nano structures. This stage might involve foraging for these materials in the forest, or growing them in a lab or at home. In this stage, designs might aid in this foraging, or the growing and nurturing of the living organisms.

-

The second stage involves turning these biomaterials into menstrual care artifacts or products, such as pads, tampons, wearable garments… or other objects that might support the menstrual cycle. Here designs could help menstruators fabricate their own products with biomaterials, or could speculate on how these products might look if fully organic.

-

The third phase is the use of the products during the bleeding phase of the menstrual cycle. Here our designs might aid in collecting or analyzing menstrual blood, understanding its components in terms of the body’s health and in terms of what contents might be nutritious for other species.

-

The final stage involves ‘disposing of’ the menstrual care products, either shredding or mixing the leftover organic materials with soil or compost, or diluting the blood with water or other nutritional components to be delivered as fertilizer for plants, or for the organic materials in the first stage. Here we could even imagine a cyclical process.

-

-

The use and scale of menstrual blood

Potentially, menstrual blood can act as a fertilizer for plants, due to its rich nutrient composition. Although it has not been a subject of scientific and clinical trials, the practice of fertilizing houseplants and domestic gardens with menstrual blood is already widespread and well documented on social media and blogs.

However, when thinking at larger scales, at scales of mass production and consumption of plant-based food and products, of extensive crops and monoculture practices of modern-day agriculture, it’s hard to imagine that menstrual blood would be sufficient; it wouldn’t scale.

Fertilizing houseplants with menstrual blood diluted in water

Fertilizing houseplants with menstrual blood diluted in water -

Material exploration: Sphagnum moss

This blog entry will be a ‘living’ description on explorations with Sphagnum moss, updated as material explorations progress.

Last fall, my friend, collaborator and moss-lover Marie Louise Juul Søndergaard introduced me to the curious connections of moss and menstruation. Many of the ideas and explorations in this entry build on our conversations and shared experiments.

-

first blog entry: designing multispecies menstrual care project

I’m opening up a blog for the project ‘Designing Multispecies Menstrual Care’, a NAVET collaboration between KTH and Konstfack. In this project we will explore the design of menstrual management technologies and services, focusing on different aspects of the experience of menstruation: the assembly and design of the products, the use, and the waste and composting of the organic materials leftover from the process.