Exploring superabsorbent biomaterials

Sanitary pad and tampon prototypes made with gluten

Sanitary pad and tampon prototypes made with gluten

During the last few weeks we’ve been meeting with Antonio Capezza, PhD in Fiber and Polymer Technology at KTH Royal Institute of Technology and Product Quality at SLU, currently doing his postdoc in the same topic, with a focus on protein-based superabsorbents for the hygiene industry —funded by Bo Rydins Stiftelse for independent research. Antonio’s work is motivated by finding a sustainable and biodegradable replacement for SAP (Superabsorbent polymer), which is a plastic-based superabsorbent that turns into a viscous gel when in contact with liquid. This fossil-based material is non-biodegradable and can lead to toxic waste and microplastic pollution.

Antonio showed us how the majority of diapers and sanitary pads contain SAP. He cut open a sanitary pad and sprinkled the powder within it on a dark sheet of paper. SAP was discontinued from use in tampons due to concerns with toxic shock syndrome, but the use of SAPs doesn’t seem to be decreasing. This material is being given new applications such as water retention agents, to aid with droughts and dry soil, and is commonly used as fake snow in the film industry, or for other medical and agricultural uses. So it seems like this remedy for climate-crisis-affected ecosystems is to introduce microplastics into the soil? I can see where Antonio gets his motivation!

As a simple experiment, Antonio showed us some samples of gluten and potato based superabsorbents and we “planted” them with soil and seeds to anticipate their biodegradability. After a few days, most of the samples started sprouting and some even started smelling like they were really decomposing.

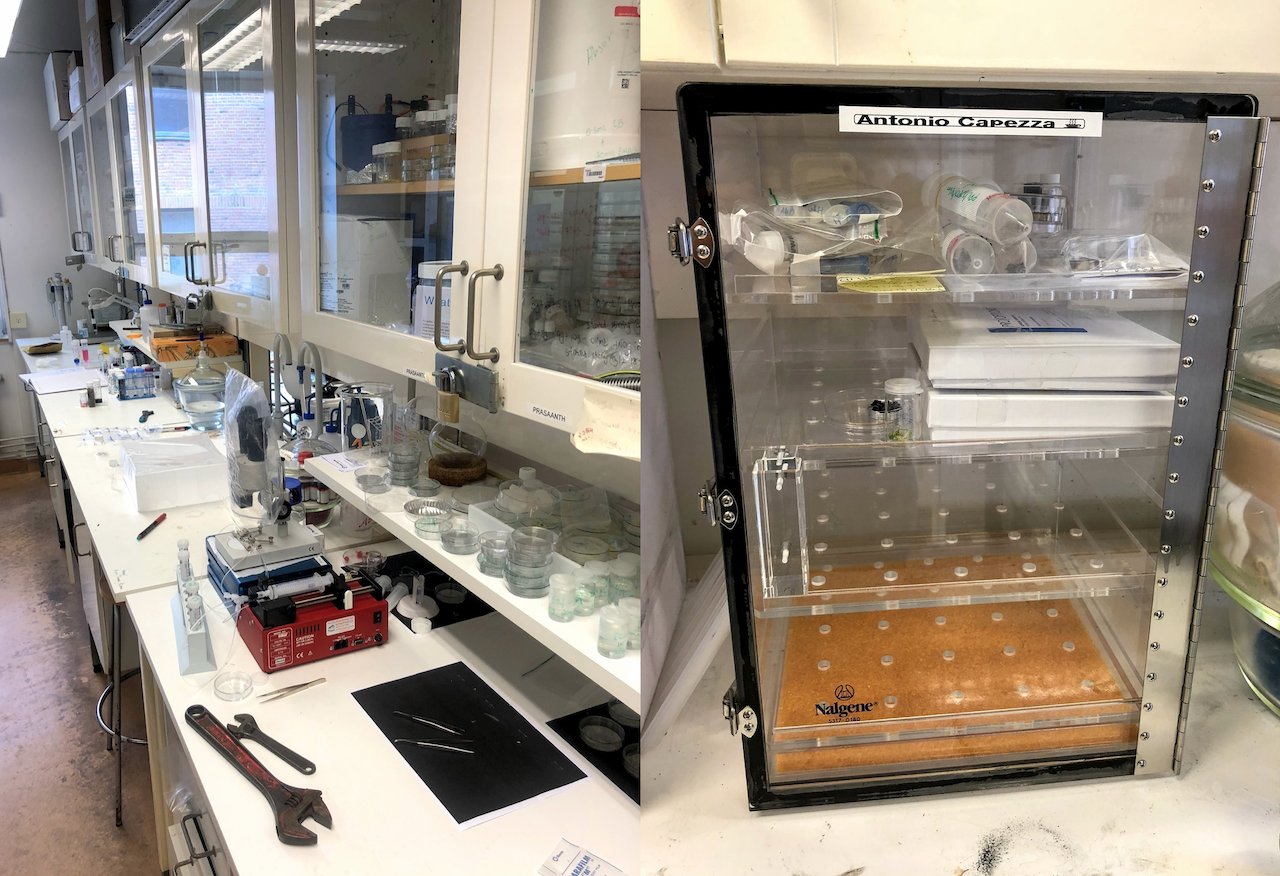

Next, we visited Antonio’s labs and got a glimpse of the spaces and equipment used in polymer science. Antonio also gave us some powdered gluten so we could get a feel for the material and start to experiment with it. He obtains this industry co-product from his industrial partners. However, gluten can be obtained easily at home by washing the starch out of normal wheat flour.

Recently, gluten has also gained some public attention via viral recipe videos that teach how to make make chicken-like fake meat from flour. This culinary practice dates way back within eastern culture, and is common in many asian cuisines (seitan in Japan, milgogi in Korea, mianjin in China etc). I learned a bit about gluten-making and it’s historical use in cooking in this video.

The gluten-water mix resulting from the flour-washing process, or by combing water with the gluten powder Antonio provided is an incredibly stretchy, springy and elastic material. It could even act as an inflatable material as long as it’s wet.

While Antonio is working on increasing the porosity and, in consequence, the absorption of this material, it is still interesting for us to experiment with the aesthetic and sensory qualities of it. As an initial exploration, I molded and shaped some of the gluten powder and let it dry to harden. The result is a very brittle cookie-pad 🍪, a questionable tampon, and some moss-gluten mix.

While this set of shapes is speculative, it might also be a first step to imagining what menstrual care with gluten might look, feel and smell like.

What does it mean that menstrual management products are not bleached white? Does it complicate understanding and observing the blood? Perhaps it challenges the notion of cleanliness and purity associated with menstruation.

Perhaps the gluten can be softer and foam-like? Or fabricated in a flexible way, much like 3D printed textiles or laser-cut curvatures. We are also very intrigued by the possibilities of making this material in the home. And how might we imagine growing and harvesting this material? Since the cultivation and processing (milling?) of wheat is commonly done at massive scales, how can we make sense of those practices at more-than-human scales?