The use and scale of menstrual blood

Potentially, menstrual blood can act as a fertilizer for plants, due to its rich nutrient composition. Although it has not been a subject of scientific and clinical trials, the practice of fertilizing houseplants and domestic gardens with menstrual blood is already widespread and well documented on social media and blogs.

However, when thinking at larger scales, at scales of mass production and consumption of plant-based food and products, of extensive crops and monoculture practices of modern-day agriculture, it’s hard to imagine that menstrual blood would be sufficient; it wouldn’t scale.

Fertilizing houseplants with menstrual blood diluted in water

Fertilizing houseplants with menstrual blood diluted in water

In this way, the use of menstrual blood as a fertilizer only makes sense at local scales, where individuals are willing and are able to collect and distribute their blood to their houseplants, urban gardens or local wild flora.

Would the monthly blood of one menstruating human be enough to nourish the crops that this human, or a small collective, would consume during the month?

When giving a ‘practical use’ like fertilizer to menstrual blood, which is commonly considered waste, and ‘useless’, one could wonder if we might we be risking turning menstrual blood into a commodity. Imagine that menstrual blood is suddenly discovered to hold the miraculous properties of organic plant nutrition, reparation of wounded or damaged skin, or as a source of serum for nourishing tissue culture and possibly lab-grown meat… Wouldn’t it suddenly be regarded as liquid gold?

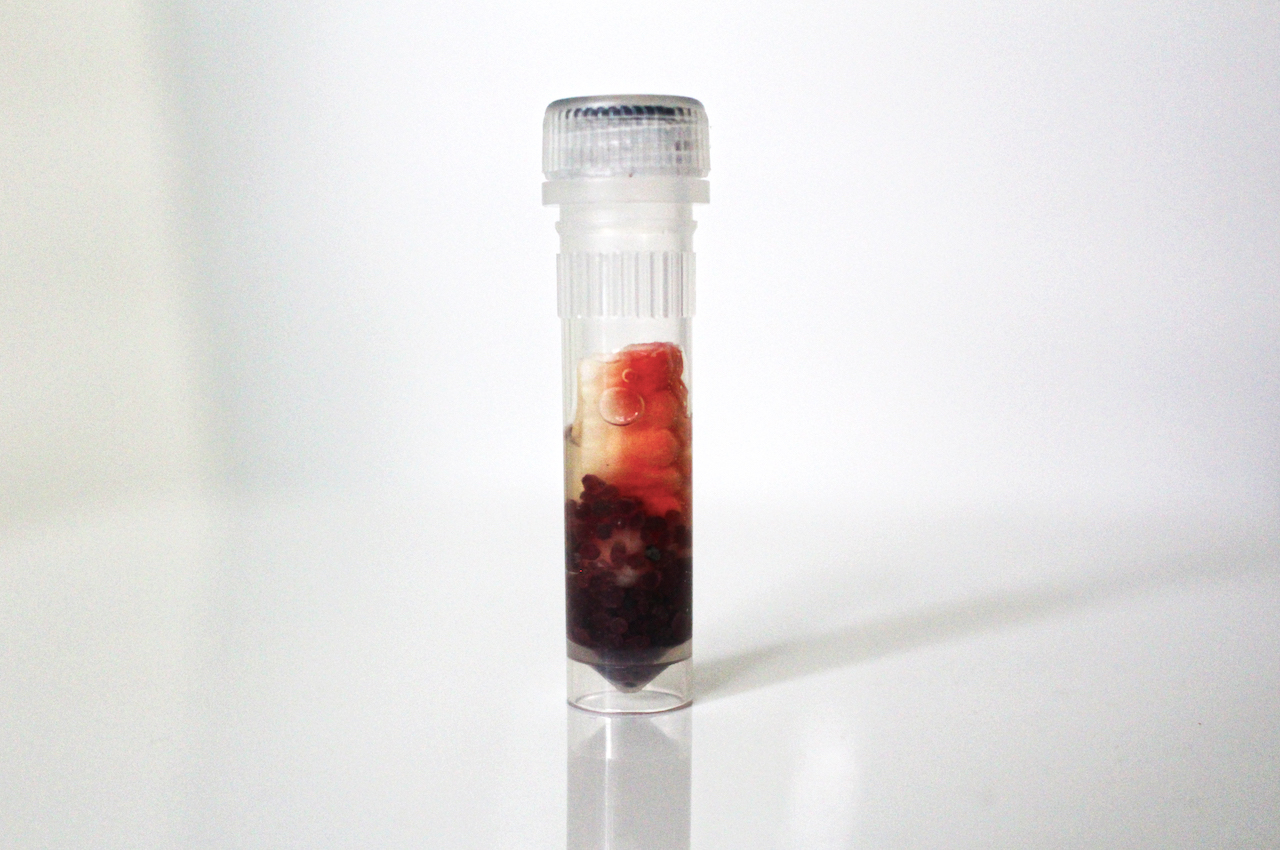

WhiteFeather Hunter, Mooncalf, 2019-present

WhiteFeather Hunter, Mooncalf, 2019-present

Wait, menstrual blood can already do all that?

Yes. Yet menstrual blood has not been harvested and packaged away by trendy silicon-valley startups, and we are yet to imagine what a multinational-pharmaceutical-company-owned menstrual blood bank would look like. This is possibly because menstrual blood carries the enormous weight of centuries of stigma, disgust and shame. The menstrual products that currently exist in the world build on this stigma, and more broadly, on the objectification and control of marginalized bodies.

I am not arguing for the commodification of menstrual blood here; quite the opposite. I am arguing that the practices of collecting, understanding, noticing and nourishing other species with menstrual blood are acts of defiance of a capitalist system, they do not fit within a system that oppresses and enforces stigmas upon menstruating bodies. Menstrual blood as ‘useful’ doesn’t fit into capitalist dreams.

In this project, it will be necessary to hold on to these reflections and keep them in mind when further in the design process. If we are not interested in scaling the use of menstrual blood, but focusing on local and communal practices, it is essential to consider designing a process or ritual rather than a product. The making is not less important than what is made, and in this case, the making, the exploration of the materiality of menstrual blood, is what could be truly radical.