knitting data

“knitting is a living tradition—it’s physical knowledge of a culture. Knowledge of language dies so quickly. It’s awesome to find a sweater and look at the language of it—to see how it’s made, what yarn was used, and how problems were solved. A sweater is a form of consciousness.” ― Sabrina Gschwandtner, Knitting is…

Last week I opened a thread on twitter asking people to share their best software + knitting references. I’ve collected all the recommendations and my own references in an Are.na board: https://www.are.na/nadia-cw/software-knitting-feminisms

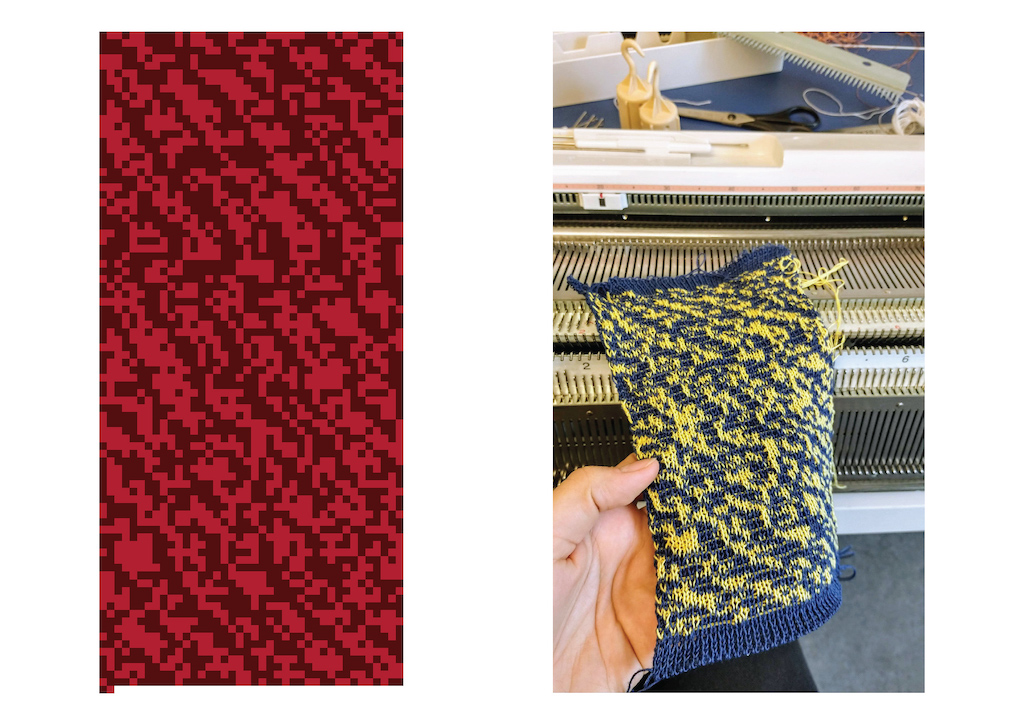

One of the first things that some of these projects do, and that seems like a pretty obvious relationship between knitting and software, is to knit binary data with two-color knitting techniques (fair-isle or double jacquard for reversible ones). Each stitch can be treated like a pixel, and the two colors represent a zero or a one. Or two types of stitches can be used, or the presence or absence of holes in the knitted piece, or any other combination of two knitting variables.

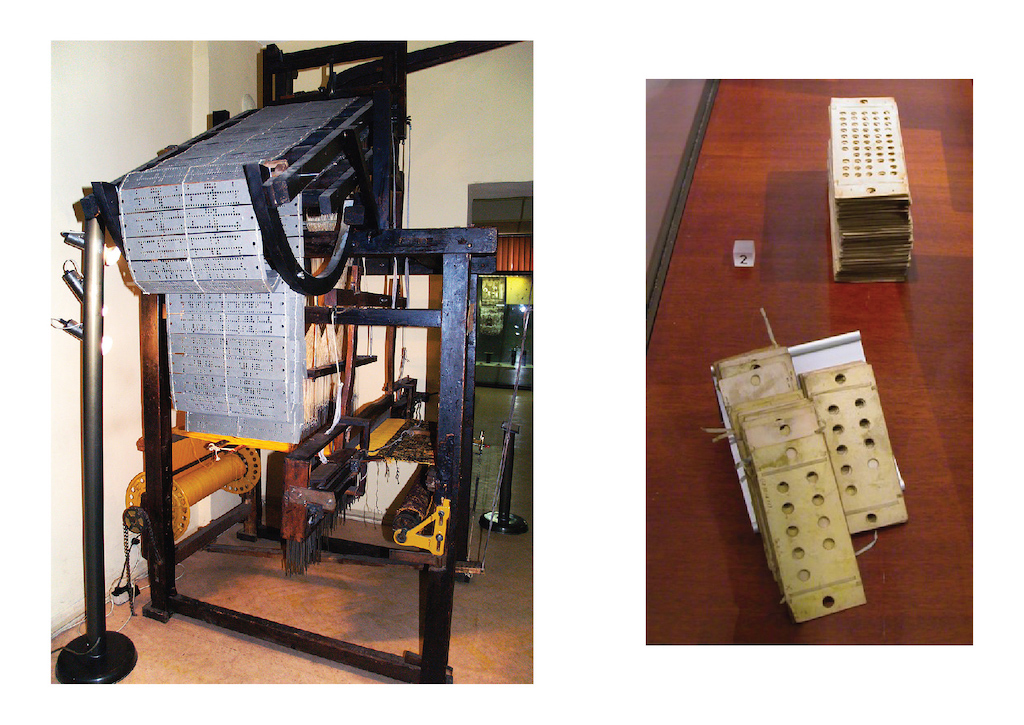

This is actually what the first instances of computation looked like, punchcards representing zeros or ones. Charles Babbage was inspired by the Jacquard Loom, which used a punchcard system, when creating the Analytical Engine, which is considered to be one of the predecessors of modern computers. Later, Babbage’s assistant, Ada Lovelace, documented and annotated the description of the machine, including an algorithm to calculate a mathematical sequence (Bernoulli numbers) using the machine. Because of this, Ada Lovelace is considered to be the first computer programmer.

“The analytical engine will weave algebraic patterns like jacquard looms weave flowers and leaves” ― adapted from Ada Lovelace’s notes from 1842.

The Jacquard loom and its punchcards (left) and the punchcards used in the Analytical Engine (right). Images from Wikipedia.

The Jacquard loom and its punchcards (left) and the punchcards used in the Analytical Engine (right). Images from Wikipedia.

The actual birth of computation, inspired by weaving and knitting, commonly regarded as “women’s work”, contrasts with the entirely masculine history that succeeds it. From the development of the first computers, which were only accessible to scientists and high ranking military (vastly white men), to the state of computer science today, computers have been associated with “men’s work”. Thus, there is a truly feminist legacy to doing work on knitting and software.

Back to experimenting with knitting data, as a first test, I made a small p5.js sketch that converts a text into binary and then creates a grid based image with two colors representing every zero (red) or one (dark red). I then used DAK to create a knitting pattern from the image and I knit the pattern with the machine (using different colors!). This Ursula K. Le Guin quote became a little piece of encoded knitting. If one was to try too decipher the knit, they would have to count every eight stitches, which is byte, translate color to zeros and ones, and then translate the binary to decimal, then look up the number in an ASCII table and get the corresponding character. There really doesn’t seem to be a point in doing this translation, there are much better and more efficient ways to store data and even encrypt it (requires a key to decode), but physicalizing binary code is an interesting experiment to help get a sense of the sheer immensity of computation. This knitted swatch was a paragraph long:

“Its technology is how a society copes with physical reality: how people get and keep and cook food, how they clothe themselves, what their power sources are (animal? human? water? wind? electricity? other?) what they build with and what they build, their medicine - and so on and on. Perhaps very ethereal people aren’t interested in these mundane, bodily matters, but I’m fascinated by them, and I think most of my readers are too. Technology is the active human interface with the material world.” ― Ursula K. Le Guin Ursula K. Le Guin: A Rant About “Technology”

Beyond binary information, there are many examples of how data visualization can be done via knitting. In these instances, knitting a row might symbolize a change in temperature, or it might indicate every time men or women talk during a council meeting (can you guess who talks more), or it could map to a baby’s sleeping pattern (the father made a piece of software that helped with the knitting) . In these cases, knitters make maps or legends of the data, and use more than two variables, using rows or stitches as variables, or treating the knitting as a canvas (one stitch - one pixel).

I started hand-knitting a scarf representing my menstrual cycle data (pink for bleeding, blue for ovulation, yellow for PMS).

I started hand-knitting a scarf representing my menstrual cycle data (pink for bleeding, blue for ovulation, yellow for PMS).

Another straightforward way to represent data via knitting is to encrypt it using existing standards or tools that allow for easy decryption or decoding, such as QR codes, which can be scanned via a smartphone. In these tests, having each pixel correspond to one v-shaped stitch didn’t seem to be a good enough resolution for the camera, because the app on my phone couldn’t recognize it. Still, it might spur interesting thoughts about what it means to knit this kind of code. What interactions could we imagine happening where a QR code is knitted into the fabric we wear? What are the implications of carrying around a piece of encrypted data, of digital information, embedded into something as personal as clothes?

One double jacquard attempt with thin yarn and two fair isle knits.

One double jacquard attempt with thin yarn and two fair isle knits.

Concealing information within already existing and common media has long been used as a way to share secret messages. I was directed to the concept of steganography by one of the professors in my lab, which is precisely “the practice of concealing a file, message, image, or video within another file, message, image, or video”. Taken to knitting, this can be done via any of the techniques mentioned above, and might have actually been a successful way to pass messages between allies in the second world war. A seemingly unbothered little old lady might sit near her window and slip a stitch every time an enemy train passed, later delivering a knitted scarf to her fellow soldiers.

“During wartime, where there were knitters, there were often spies; a pair of eyes, watching between the click of two needles”, from the article: The Wartime Spies Who Used Knitting as an Espionage Tool.

Knitting data therefore intersects software, crafting, gender, activism and politics. We can find many frequent examples of “knitivism” or “craftivism” such as yarn bombing, as well as artistic expressions responding to or problematizing the role of women during times of war: “[…] no longer are women seemingly protesting through their knitting, but rather their knitting contributes to wartime activity.” Knit for Defense, Purl to Control – InVisible Culture

While in 2020 we might not be confronted with the hardships of war, we are being confronted with a different kind of violence, causing harm against the bodies of those deemed vulnerable. Which leaves me with one of the questions I will be exploring: How might we use knitting and software as an activist and feminist act in our times?